The simple tale of two children, a hill, a pail of water, and a tumble has been etched into the minds of generations. We all know the words: "Jack and Jill went up the hill..." But behind this seemingly innocent nursery rhyme lies a surprisingly complex and often debated past. Unpacking the Origins and History of Jack and Jill reveals not just the evolution of a beloved verse, but also a glimpse into centuries of cultural shifts, historical events, and the human desire to find deeper meaning in the familiar.

For a rhyme so ubiquitous, its precise beginnings are remarkably hazy. Was it a playful jingle, a political satire, or a somber historical echo? Let's journey back in time to explore the curious case of Jack and Jill.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways on Jack and Jill's Origins

- Ancient Roots: While the rhyme as we know it emerged in the 18th century, "Jack and Jill" were generic names for a boy and girl as early as Shakespearean times (late 16th century).

- First Appearance: The earliest known published version appeared in a reprint of John Newbery's Mother Goose's Melody around 1765.

- Original "Gill": In early versions, Jill was spelled "Gill," and illustrations sometimes depicted two boys.

- Evolution of the Story: Over time, additional verses, moralizing chapbooks, and different plot points (like parental whippings) were added, especially in the 19th century.

- Musical Legacy: The rhyme gained its popular melody through James William Elliott's 1870 collection and has been set to music numerous times since.

- Contested Origins: Many theories abound regarding its true meaning – from Norse myths to political satire against King Charles I's taxation, or even a local tragedy in Kilmersdon, England. Most lack definitive proof.

- Enduring Appeal: Despite its uncertain origins, "Jack and Jill" remains a powerful piece of cultural heritage, adapting and resonating across generations.

The Rhyme You Know (and Maybe Don't)

Before we delve into its murky past, let's revisit the familiar verses that have shaped our understanding of Jack and Jill. For many, these are the lines that instantly come to mind, a standard that solidified in the 19th century:

"Jack and Jill

Went up the hill

To fetch a pail of water.

Jack fell down

And broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after.

Up got Jack, and home did trot

As fast as he could caper.

He went to bed and bound his head

With vinegar and brown paper.

When Jill came in

How she did grin

To see Jack’s paper plaster;

Mother vexed

Did whip her next

For causing Jack’s disaster."

These stanzas, often sung to a distinctive tune, paint a vivid picture of childhood mishap, a touch of schadenfreude, and a swift, albeit harsh, maternal justice. Yet, this version is far from the whole story; it’s merely a snapshot in a much longer narrative.

From "Gill" to "Jill": Tracing the Earliest Footprints

The journey to understand the origins of "Jack and Jill" truly begins in the 18th century. But first, let's clear up a common misconception: the names "Jack" and "Jill" themselves didn't originate with the rhyme. Long before children were singing about broken crowns, "Jack" and "Jill" were generic terms in English, much like "Tom, Dick, and Harry," used to refer to any boy and girl. William Shakespeare, for instance, employed these terms in his plays as early as the 1590s, indicating their widespread use in popular speech.

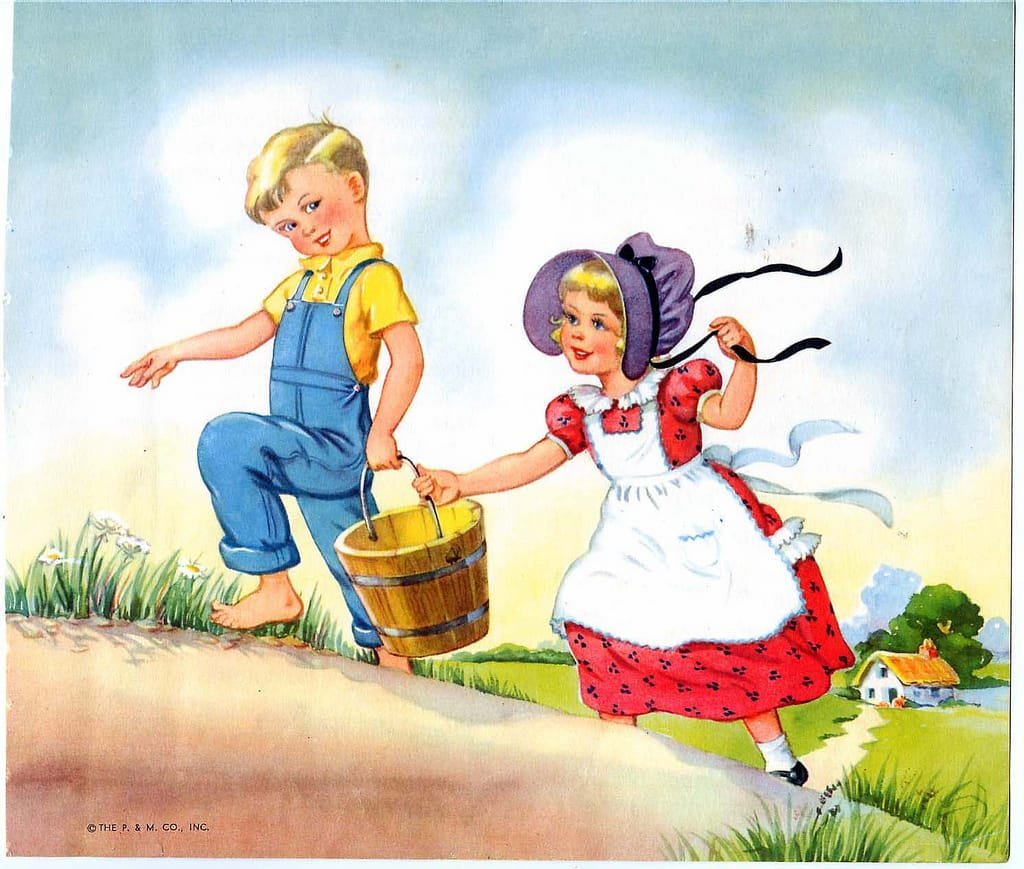

The actual rhyme, however, makes its public debut much later. The earliest known published version surfaced in a reprint of John Newbery's Mother Goose's Melody, believed to have first been published around 1765 in London. This seminal collection of nursery rhymes cemented many verses in the public consciousness. Intriguingly, in this initial printing, Jill was spelled "Gill," and an accompanying woodcut illustration didn't even feature a girl. Instead, it depicted two boys. This detail suggests a fluid understanding of the characters and their genders in the earliest iterations.

The rhythmic quality and specific word choices offer further clues. The rhyming of "water" with "after" in the first verse, for example, is characteristic of 17th-century English pronunciation, hinting that at least this initial couplet might predate its 18th-century publication by several decades, passed down through oral tradition. This fascinating tidbit provides a window into the dynamic nature of language and how rhymes can evolve over generations before being captured in print.

The Story Expands: More Falls, More Lessons

The 18th-century Mother Goose's Melody gave us a concise, often one-stanza version of Jack and Gill's misadventure. But the 19th century, a period of burgeoning children's literature and moral instruction, saw the story of Jack and Jill expand dramatically.

In 1806, a chapbook titled Jack & Jill and Old Dame Gill stretched the narrative to a hefty 15 stanzas. This expanded version wasn't just longer; it introduced new mishaps involving a dog and a goat, culminating in the mother's whipping – a stark reflection of the era's attitudes towards discipline and didactic storytelling. This marked a significant shift in children's literature, moving beyond simple rhymes towards more elaborate, entertaining, and often moralizing tales.

The popularity of Jack & Jill and Old Dame Gill spawned numerous pirated editions between 1835 and 1845, each with slight variations in wording, illustrations, and even additional creatures joining the fray. One 1840s edition from Otley, The adventures of Jack & Jill and old Dame Jill, went further, using longer, more circumstantial quatrains and even altering Jack's treatment from the traditional "vinegar and brown paper" to "sugar and rum" – perhaps a nod to more palatable, if less medically sound, remedies of the time.

American adaptations also contributed to the rhyme's evolution, frequently injecting overt moral instruction. Fanny E. Lacy's 1852 Boston version and Lawrence Augustus Gobright's 1873 Philadelphia adaptation are prime examples. Gobright's take even depicted Jack and Jill as a devoted married couple, transforming their childish antics into a parable of adult partnership, albeit still fraught with domestic mishaps. Later, more whimsical adaptations like Margaret Johnson's "A New Jack and Jill" in Saint Nicholas Magazine imagined a bucket with a hole, while Clifton Bingham's "The New Jack and Jill" (1900) reintroduced the now-familiar six-line stanza form.

These successive adaptations underscore how "Jack and Jill" wasn't a static piece of folklore but a living story, continually reinterpreted and reshaped to reflect the changing values, literary tastes, and educational goals of each new generation. To explore more about how the rhyme has been reimagined and understood through different cultural lenses, you might find Our complete Jack plus Jill guide particularly insightful.

A Song in Every Style: Musical and Artistic Life

The enduring appeal of "Jack and Jill" extends beyond its lyrical permutations; it has also captivated musicians and artists, embedding itself deeper into the cultural fabric.

One of the earliest musical arrangements for the rhyme was a catch published by Charles Burney in 1777, showcasing its potential for vocal harmony even in its nascent form. However, the melody most commonly associated with "Jack and Jill" today – the one that likely plays in your head as you read this – was first formally recorded by James William Elliott in his influential collection, National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs, published in 1870. This publication was crucial in standardizing the tune, allowing it to spread widely and become a staple in homes and schools.

Artists also found inspiration in the simple narrative. Walter Crane, a prominent figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, illustrated a single-stanza version in his beautifully rendered The Baby's Opera (1877), helping to visualize the characters and their setting for countless children.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, composers continued to adapt the rhyme. Victorian composer Alfred James Caldicott transformed it into a part song in 1878. Further adaptations followed from E. M. Bowman (1883), Charles R. Ford (1885), and Spencer Percival (1882), each offering their unique musical interpretation. By the 1920s, the rhyme was even subject to playful parody, with Sigmund Spaeth creating various musical style interpretations in The musical adventures of Jack & Jill (1926). Even in more contemporary settings, the rhyme continues to inspire, as seen in Geoffrey Hartley's 1975 chamber piece for horn and two bassoons.

These musical and artistic contributions highlight the rhyme's versatility and its power to transcend its humble origins, becoming a canvas for creative expression across different mediums and eras.

Unraveling the Mystery: Competing Theories of Origin

Despite its straightforward narrative, the true origin and meaning of "Jack and Jill" are subjects of lively debate. Many theories have been proposed over the centuries, often attempting to connect the rhyme to significant historical events or deeper symbolic meanings. However, it's crucial to approach these interpretations with a critical eye, as many lack concrete corroborating evidence and often emerged long after the rhyme's first known publication.

Let's explore some of the most popular and intriguing theories:

Norse Mythology: The Moon's Children

One of the more ancient and intriguing suggestions comes from S. Baring-Gould, who in the late 19th century proposed a link to Norse mythology. He drew parallels between Jack and Jill and the figures of Hjuki and Bil from the 13th-century Icelandic Gylfaginning. In this myth, Hjuki and Bil, a brother and sister, were stolen by the Moon (Máni) while they were drawing water from a well, carrying it in a pail.

The imagery of children fetching water and being taken away certainly echoes aspects of the rhyme. However, beyond this superficial similarity, direct evidence linking the Norse myth to the English nursery rhyme is tenuous. It's a compelling idea, suggesting a deep, ancient root for the motif, but it remains speculative.

Historical Figures: Tales of Treachery and Taxation

Some theories attempt to tie Jack and Jill to specific historical figures or events, often with a darker undertone than the rhyme itself suggests.

- Empson and Dudley (1510): One interpretation points to the executions of Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley in 1510. These two highly unpopular tax collectors for King Henry VII were arrested and later beheaded by Henry VIII, who was keen to distance himself from his father's less popular policies. The "fall" of Jack and Jill could metaphorically represent the downfall of these figures.

- Thomas Wolsey (1514): Another theory, less common, briefly mentions a marriage negotiation by Thomas Wolsey in 1514, though details linking this specifically to the rhyme are scarce.

While these historical events certainly involved dramatic "falls" from power, connecting them directly to a children's rhyme written centuries later requires a significant leap of faith without concrete textual or historical proof.

King Charles I and the Taxation Theory

Perhaps the most famous political interpretation involves King Charles I and his attempts to raise revenue. This theory suggests the rhyme is a satire of a parliamentary act by Charles I that sought to raise revenue by reducing the volume of a "Jack" (a common measure, 1/8 pint) of beer, while the tax remained the same. Subsequently, the "Gill" (a quarter pint) would "come tumbling after" in its reduced volume and increased price.

- "Jack fell down and broke his crown" could refer to the King (whose head wore the crown) losing popularity or power due to these unpopular measures.

- "Jill came tumbling after" would represent the smaller measure of alcohol and the common people suffering the consequences.

This theory offers a clever linguistic and historical connection, but again, it largely postdates the actual political events by over a century and lacks definitive contemporary evidence to confirm it as the rhyme's original intent. It's a compelling historical "what if," rather than a proven fact.

The Kilmersdon Village Tragedy

In the village of Kilmersdon in Somerset, England, a poignant local legend links the rhyme to a specific, tragic event. According to this belief, the rhyme commemorates a local girl named Jill who became pregnant by a young man named Jack. The story goes that Jack tragically died from a rockfall while fetching water from a local spring on the hill, and Jill subsequently died in childbirth.

The village has embraced this lore, with six stone markers placed on a local hill, each bearing a verse of the poem. A well and a plaque are also dedicated to Jack and Jill. Furthermore, the local surname Gilson is thought by some to derive from "Gill's son." This theory is deeply embedded in local culture and evokes a powerful sense of place and personal tragedy. While it provides a romantic and mournful origin story, historians generally regard it as a folk etymology or a retrospective association, meaning the village likely adopted the popular rhyme and created a local legend to explain it, rather than the rhyme originating from the specific Kilmersdon events.

The Prosaic Origin: Dew Ponds and Daily Chores

In stark contrast to the dramatic and tragic theories, historian Edward A. Martin suggests a much more mundane, yet practical, origin for the rhyme. He notes that in rural areas, pails of water were often collected from "dew ponds" – artificial ponds constructed on hilltops to collect rainwater and dew for livestock.

This "prosaic origin" posits that Jack and Jill simply represent ordinary children undertaking a common chore in a common landscape. Their fall is a simple, everyday accident, a relatable mishap rather than a coded historical allegory. This perspective reminds us that not every piece of folklore needs a grand, hidden meaning; sometimes, the most profound stories are those that mirror everyday life.

King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

Another popular interpretation, particularly in France, links the rhyme to King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution. In this grim reading:

- "Jack fell down and broke his crown" refers to King Louis XVI losing his head (crown) via the guillotine.

- "Jill came tumbling after" refers to Marie Antoinette, who followed him to the guillotine shortly thereafter.

While historically evocative, like many other theories, this interpretation suffers from a chronological mismatch. The earliest known English version of the rhyme predates the French Revolution (1789-1799) by at least two decades, making it unlikely to be the original inspiration. It is, however, a powerful example of how folk tales can be reinterpreted to reflect later historical traumas.

Why These Stories Endure: The Deeper Resonance of Jack and Jill

So, what is the true origin of Jack and Jill? After sifting through the evidence, the most honest answer is that the definitive origin remains uncertain. Most of the compelling, dramatic theories connecting the rhyme to specific historical events or figures lack concrete evidence that pre-dates the rhyme's publication. They are more likely popular reinterpretations or local legends that sprung up after the rhyme became widely known, rather than its original source.

The most reliable information points to a gradual evolution:

- Generic names for a boy and girl were already in use.

- A core verse with a recognizable rhythm and rhyme likely existed in oral tradition by the 17th century.

- It was first formally published in the mid-18th century, with "Gill" and simple illustrations.

- It expanded and adapted significantly in the 19th century, reflecting changing societal norms and literary tastes.

Despite the ambiguity, the very existence of so many competing theories speaks volumes about the enduring power of "Jack and Jill." It highlights our innate human need to find meaning, to connect the stories of our childhoods to the grand narratives of history, and to uncover hidden depths beneath seemingly simple verses. Whether a mundane chore gone wrong, a coded political protest, or a tragic love story, Jack and Jill's journey up that fateful hill continues to resonate, reminding us that even the simplest rhymes can carry complex echoes of the past.